Buttons

Buttons have stories to tell – given any random button to hold in your hand and it’s highly likely that we can remember which garment it came from, even if we last saw it or wore it many years ago. The inherited button box has always been a fascination for small children, it’s a repository of memories, and for us, a great source of material for new projects. Why not take that beautiful Victorian hand paint button from it’s box and fix it to a lampshade or a curtain where it can be enjoyed daily ?

Buttons are firstly functional- they have a job to do, and then as is the nature of man, anything that stays still long enough gets decorated. So buttons have been painted and moulded, fabric covered, made from glass or ceramic, metal or wood, nuts or seeds and in all manner of sizes and shapes. And this is their joy, even when there are rows of the same for sale, we can find other buttons – on antiques stalls, those that were once made for the wealthy alongside those painted by gypsies, and then at crafts fairs new buttons, made by a local potter or ceramicist. Or we can make our own.

Buttons are secondly decorative – they create mood and atmosphere, so they are special. Throughout the fashion and furnishing worlds buttons have high presence, being carefully considered, designed and positioned to convey personality. We’ve all surely changed the buttons on a high street jacket to make it just that bit more special, unique. And so it is with furnishings – buttons alone can make the back of a thing look every bit as good as the front.

Collecting buttons from earlier garments and antiques market stalls is an enjoyable past-time that won’t break the bank; buttons can be used and enjoyed immediately, just for decoration even if you have no closure project in mind. I’ve got some really beautiful creations from a stall in the Bath antiques market–they are whole sets still in the makers’ boxes, displayed like exquisite pieces of jewellery: they weren’t given away by any means, but I love them and wish I could have stretched to a few more!

Also keep an eye out for buttons made from recycled materials such as glass and leather, paper and plastics, bottle tops and scrap metals. These buttons may not be elaborate but they are hand made and carry something of the makers hand and individuality. When we use wooden and glass beads and buttons from small African village workshops it just adds something to the work and the global spirit, when we realise, or remember, that these have their stories too. They have been formed or painted by a real person and not a machine – a mother, a boy or a girl sitting in community, under the sun of a remote village, making things that are used and enjoyed in my world, which is as remote to them as theirs is to me.

A few years ago I bought a collection of handmade buttons from a lady whose father had been a button maker to the couture world, so each of these had been made with a particular garment or designer or client in mind. They are over-runs and seconds, special and unique, and a constant source of inspiration as we imagine the type of garment, the fabric and construction that might have been the design driver.

With the internet, the button market has become global, so finding amazing and beautiful buttons and button dealers is very easy; however, if you have the time and the inclination, there’s still nothing like a good rummage through country sales or craft fairs to make your own finds.

Searching out unusual and indigenous buttons on holiday is good fun, an ancillary pastime that may even add a greater sense of purpose to an excursion. Buttons and beads are pocket buys, they’re easy to carry, useful, and a constant reminder of a great experience. You can’t ask for more than that!

And who can’t resist the lure of Murano glass beads from Venice ? Collecting a few at a time from the small shops that line the lanes radiating from St Marks square – for necklaces but also for buttons, to weight cords or to finish off the ends of ties.

Button closures

* I guess the zipper took over from the button because it’s more reliable, and certainly people don’t much like making buttonholes, as they are a bit of a fiddle. But then it’s not that easy to set a zip really well.

* For all visible openings, and especially for cushion and loose covers we always prefer to have some sort of buttoning or ties over zippers.

* Cushions especially are so much more pleasing if they’ve been designed without ugly zips; in our house–even with housekeeping help–it’s virtually impossible to assume that cushions are always placed with the zip down, or even with the front showing…And I know I’m not alone in this as I’m always turning cushions over or zip down in clients’ homes.

* I can never comprehend why loose covers are so often made with zip side closures, or even worse touch and close tape? There is nothing more ugly, especially as it’s not a given that these closures are out of sight: the backs of sofas and chairs are as likely to be in the middle of a room as against a wall. A row of buttons would look so much better- and for such a relatively low percentage of time.

Closure buttons work with rouleau loops, buttonholes , eyelets, frogs, laces and ties. With the basic skills under your belt and some design inspiration, button world is your oyster !

Placement

Once the decision to use buttons has been made the placements can be as imaginative as the function allows. For example a row of tiny buttons used as a closure will be different, but not necessarily worse than say, 2 over- sized ones.

It goes without saying that spacing and button size must relate to the complexity and proportions of the project; however all rules can be broken, and as long as they still do the work, buttons can virtually disappear, become a real feature, work in groups or series, or even have non functional buttons mixed in.

Positioning buttons

* Buttons should always be placed along the centre line of the closure allowance

* Always place the buttons onto your work before you even think about making buttonholes or placing the opposite part of the closure.

* If you want to use an oversized button, you need to allow extra width from the closure edge, rather then moving the button away from the centre line. If you chose the button late, it’s better to add a facing than move the button line.

* A neat row always looks good, however pairing and clever spacing can half the making time.

* For good proportion and balance a general rule is that large buttons should be spaced further apart than small ones.

Buttoning

In furnishing terms, ‘buttoning’ generally refers to the method of stitching through layers of horsehair to make cushion pads and chair arms and backs; the tufts, or buttons are the decoration that cover the stitches. This button covered stitching can be shallow, just enough to make an indentation in the work, or deep, creating fabric fullness between each button that is pleated away – as we can see on bed heads, chair and sofa backs and seats, mattresses, fixed seat cushions and boxed cushions used as seating.

The ‘buttons’ might be made of any material including circles of fabric or leather, or wool tufts. Buttons with shanks are often self covered so that the shape created by the stitching forms the pattern – this is usual for buttons set deeply within any material, creating a sort of soft sculpture. But it’s not compulsory and any deep buttoning can either be self covered and dense, or reflective – made of tiny metal studs, glass or crystal beads that reflect light.

When buttoning is more practical than decorative, the buttons need to work harder to create one sort of impact or another, and here your imagination can take flight. Some alternative ideas to the expected idea of buttons are beads, crystals, gaming counters, coins, coffee beans, stones–anything that’s not sharp and that you can drill a hole through.

BUTTON TYPES

Sew through:

These are the the ones we experience on every day-to-day shirts and jackets. Two, three or four holes are pierced through the centre of the button to provide a means of fixing them. As the stitches hold the button very close to the fabric these buttons are ideal for our purposes unmaking buttoned borders, for plackets and for closures, as well as for surface decoration. For ease of use however, you need to make a shank from thread that is at least as deep as the buttonhole and with enough lea-way to allow the button to turn easily as you fasten and unfasten it.

You can make the shank by eye when you have some experience, but a readily available matchstick, or tapestry needle make good spacers. Start from the right side and secure the thread, then take the thread through the button and over the matchstick or needle that is held on top of the button. Make several stitches, take the spacer out and lift the button to the extent of the thread loop. To form the shank, now wind the thread tightly around the threads beneath the button. Secure the threads by backstitching into the shank, run the thread away between the fabric, layers, secure and cut off.

If the fabrics need any extra reinforcement – a fine fabric will already have been interfaced – make a neat square of the same material beneath each button and stitch into this.

Shanks:

Shank fittings allow the button to be seen without thread interruption and so are always used for ball and domed shaped buttons; for deep buttoning the shank is used to pull the button right into the well and as close to the fabric as possible. Always look at the depth of the shank to make sure it’s suitable, however should your button of choice not be perfect and if you need the button shank to be longer, you can always extend it with cord or fine ribbon.

If the shank is too deep the button will wobble around, the back will become visible and it won’t look or sit well in its buttonhole. To limit this, line up the shank with the direction of the buttonhole and attach it using small stitches; if it’s wobbly or you want to ‘shorten’ the shank add button hole or blanket stitches all the way around; these act to decrease the shank and pull it back into the fabric.

If you’ll need to remove these buttons for washing, you can make them to be detachable. Make small eyelets in the main fabric, push the shank through and fix it at the back with a small toggle, a pin from the back of the button card, a small safety pin, or stitch a flat button to it.

Studs:

Studs are not buttons but can be used in place of, with the dual advantage that they don’t require a buttonhole to be worked and that they remain exactly where they are pinned. As well as the more obvious jacket studs and anything available from the haberdashery racks, look to the camping and yachting world for inspiration and for larger scale studs. Earings, broaches, hat pins and cufflinks are all types of stud that make fantastic alternative buttonings.

To fix studs, either pierce the fabric with the given pin and fix it to the back, or make a small eyelets to accommodate the shank and fix the back with a toggle or a security pin

Beads:

Beads are not intended to be buttons, but they can work as such extremely well– all that’s required is that you make the shank yourself. To do so, secure the thread and take it through the bead, then back into the fabric. Ease the bead away from the fabric, far enough for a shank to be created beneath the bead; allow enough length to accommodate the depth of the buttonhole or tie, plus 3 mm ( 1/8″). Wind the thread around this core a couple of times to hold the bead in position, make three-four more stitches to secure the bead, wind the thread around the length of the shank, secure with back stitches into the shank and take the thread away before cutting it.

REINFORCING

For heavy use projects with fine materials such as duvets and for denser fabrics such as denim, gabardine, or corduroy, you might feel inclined to reinforce the button stitching. Where the button back won’t be seen, you can use a small square of the main fabric, or a non fraying felt in a similar colour; place it behind the button and take all stitches right through to the back of the reinforcing square; trim it back until it is just the size needed.

Where the button back will be seen, place a small, flat button on the back and stitch this in place each time the threads come to the back. For duvets and pillows, cotton covered housekeepers buttons or simple shirt buttons work quite well as reinforcing buttons.

LINKED BUTTONS

These operate in the same way as cufflinks. In fact cufflinks of any ilk and design are a very good option for special cushion closures and lampshade details; and especially when the cushion is a gift. It’s a fun idea to make the cushion the vehicle for the gift…..the cufflinks.

To join two buttons using a stitched shank

a) run several threads between the buttons leaving the linking threads between them long enough to do the work needed, plus 3mm ( 1/8″ ) for ‘shrinkage’. Work close buttonhole or blanket stitches along the length of the link to make a good looking shank; the stitches should be very neat and dense. Run the thread through beeswax if it keeps twisting and knotting prematurely.

b) stitch a narrow ribbon between the buttons to connect them. Fold the ends of the ribbon under at both ends and stitch one button securely to each of the doubled squares of ribbon.

COVERED BUTTONS

There are kits available in several convenient sizes that make covering buttons with fabric a straightforward process. However, they aren’t without their problems and if you want a different size or prefer to do without the harsh metal or plastic teeth and shank, you could make them as they used to be made before kits were invented. The major benefit to this is that you can use fabrics that the kits don’t easily accommodate –voile, lace, velvet, fur, leather, etc.

You can make covered buttons in three similar ways: with a ring to form the shape, with a flat circle of stiffened fabric or fabric covered card, or with both the circles and the ring.

a) The ring:

Select a plastic or brass ring (use plastic only if the item will require frequent washing ) and cut a circle of fabric to just under twice the diameter. Run a gathering thread–a row of neat small running stitches–around the perimeter, as close as you can to the edge without the material fraying away. Insert the ring and pull up the gathers; secure the threads and stitch across the gap a few times to make the base for a shank. Working from the front, stitch a row of tiny, even stab stitches just inside the ring–or for a further challenge, embroider a small motif, a tiny flower, star or emblem in the centre.

b) The flat circle:

Cut a circle of firm interfacing: linen, wool melton or buckram–one that will launder without collapsing–and another of domette interlining or wool melton; cut a circle of the button fabric to just under twice the diameter. ( If you want the top to be a bit softer, perhaps slightly domed, also cut a circle of wool interlining or polyester wadding to sit closest to the face fabric. )

Run a gathering thread–a row of neat small running stitches–around the perimeter, as close as you can to the edge without the material fraying away. Insert the two circles with the softest one closest to the face fabric and pull up the gathers; secure the threads and stitch across the gap a few times to make the base for a shank. Work any stitched decoration on the front ,

c) For a button with more depth and softness, fit the ring on top of the fabric circles and make them up. image

d) To cover the back:

Cut a circle of fabric; if the face fabric is thick or in any way unsuitable, use a scrap of tightly woven linen the size of the inner diameter plus 6mm ( 1/4″). Run a gathering thread around 1/8″ from each side; pull up slightly so that the edge folds back on itself; pin to the underside of the button and secure to the first cover with tiny slipstitches.

e) To fit:

Fix it in place with a thread or ribbon shank to suit the thickness of the fabric or buttonhole.

SHOW BUTTONING

In some cases buttons are just for show. If you want to use something that looks the part but is inconvenient to use–say with rough edges that might snag, such as stones or large crystals or an uneven shape that might tear–just stitch the ‘button’ to the buttonhole, i.e. take the shank to the back and secure it. Stitch press studs just below the button and buttonhole and use these instead. The reason to still go to all the trouble of making the buttonholes is to keep it looking authentic and convincing.

THREAD

Button thread is thicker and stronger than seam stitching thread and is often doubled. A traditional tailoring technique is to draw double thread through beeswax, which prevents them from separating , kinking and knotting as you work. It’s best to use enough thread for just a couple of buttons at a time, you don’t want to risk weakening it.

Always secure the threads with a double stitch on the face, beneath the button, so that they are covered–or behind if the fabric is very fine. Don’t use knots, they’re too bulky and unreliable.

Buttonholes

Buttonholes are as useful for holding ties and ribbons, even lattice, as they are for buttons. They always look lovely en masse, especially when hand stitched, but can be a bit scary to make – they need to be exactly the right size for the button, and the stitches must be small and neat. Hand stitching looks by far the best, but takes time and some experience of handling fabrics. Machine set buttonholes make light work of the job, but are only as good as the settings given. Buttonhole thread is stronger than sewing thread and easier to manage than doubled thread.

Basic, Informal Buttonholes

Simple round buttonholes can be good options, and certainly often historically accurate – they may be found on country pieces- nightwear, smocks, flour sacks etc. And interestingly they don’t look too bad if the stitching is uneven. These are a bit ad-hoc, so to get the size right for your button and your fabric, first practice on spare piece. These buttonholes need to be flexible, so a simple blanket type stitch is used rather than the more formal buttonhole stitch with its knotted edge.

1. Mark the buttonhole positions by marking the centres of the buttons.

2. Make a hole with small scissors, a punch or awl that is approx. 2/3 the size of the finished buttonhole.

3. Secure the end of buttonhole thread into the work with a few small running stitches close to the cut edge.

4. Make a neat blanket stitch, pulling it so that the raw edge is pulled in slightly. Work neat, close stitches all the way around, and finish off with a neat double stitch and take the thread away through the stitches.

5. Steam press from the front, to embed the stitches, then from the back.

* For a more formal option, that is too inflexible for a button but perfect for tie or just decoration, make the stitches over a small brass ring.

Handstitched Formal Buttonholes

Use these for all smart work, where the buttonholes matter and especially where there is a lovely neat row, which is itself decoration. Unless you are extremely experienced the same combination of button and fabric will not have occurred before, so as these need to be neat and tidy always practice a few first.

1. Place the button onto the work, mark two ends with pins, note the centre line then take the button away.

2. Tack two rows of running stitches the length of the button, plus one thread and just about 2 mm either side of the centre line.

3. Cut the hole along the grain, centered between the threads and to the exact length of the button.

4. The buttonhole has two ends – the pulling end, the end that the button will be, when under pressure and the other, visible, end.

5. Start from the outer, or visible end.

If you’re right handed start from the lower left hand corner and make the stitches towards the right. Secure the end of the thread into the back of the work with a few running stitches between the slit and the tacked line. Bring the thread around, from right to left and under the point of the needle, then bring the needle out through the loop, so that the knot now formed will lie at the very edge of the cut.

6. Work these stitches to the end, stitch the stitches around to form a neat semi circle. Continue along the opposite side; make a bar of stitches at each end, the knotted end towards the slit.

Tip! For a fraying material: wet the slit as soon as it has been made, add a touch of pva glue (use an artists, lipstick or tiny eye-shadow brush) to the raw edges and lay a thread long the edge to use as the firm edge of the slit.

Option! For raised buttonholes lay a few threads down alongside the cut edge, hold them in place with a few cross stitches and make the buttonhole stitches over the threads, so that the finish is slightly raised.

Buttoning

Buttoning changes the character of any item – whether it’s a cushion, pelmet or a window seat pad. The extra dimensions of light, shadow, and softness are created by the indentations and changes of depth.

The purpose of buttoning is primarily to hold the filling of chair pads, window seats, mattresses, bedcovers etc. in place, and the method is as simple as a strong stitch or knotted thread. The means though, invites decoration.

* Button tufts as circles of fabric, or loops of woollen thread, are the traditional finishes and these can indeed be the best looking, however there are so many options that it is often worth investigating a few more.

* The pattern of buttoning is important – the spacing and the position – how close to the edges, how many rows, how close together are all to be decided, by marking out a template.

* The depths of the buttoning crevices will depend partly on the robustness of the materials used, how easy it is to pull the thread through and the buttons in, but also on the look that is required. Deep crevices are not so comfortable to sit on as the work creates quite a firm surface- very good for bedheads and stools, walling and screens – just not so much for sofas and chairs. The excess fabric created from the depth requires managing and is always pleated between buttons – to the row above and the one beneath, often in a diamond-shaped pattern which gives deep buttoning a distinctive look and particular decoration which can be very beautiful. Floating buttons are those that just sit, float in fact, on the surface. Pointless. And irritating. Shallow buttoning, between the two, has the means to create pattern and sculpture without the problems created by with deep buttoning – it’s enough to show the fabric off well, adding new dimensions and movement whilst remaining soft as well as showcasing the buttons.

* Self covered fabric buttons are smart and chic, the least obvious, that allow the form of the buttoning pattern to take the credit.

* Buttons can be used deliberately – to direct the eye or to create a more interesting form that the one given, to redress an imbalance.

* Add a touch of glitz and glamour by using buttons made from glass, crystals, horn or leather.

* Extra tiny buttons are as effective in their dimunitive size as over–large ones, even the tiniest crystals or small baby buttons.

* Extravagant buttons on a simple fabric such as wool melton make a bold statement.

* Hand–made and painted buttons add individuality, personality .

*Think outside the box: you can use other media to make the buttons, such as pebbles, beads, nutshells, silk roses, etc.

Buttoning

1. Find the centre of the pad at the top and the bottom and define the place with crossed pins, then stitch with coloured tacks.

2. Always make a buttoning template on calico or muslin.

To do this, cut a spare piece of calico to shape and slightly larger ( approx. 5 cms ) than the area to be buttoned. Experiment, test the spacing possibilities by marking potential button positions with crossed pins. When the design looks good, lay it over the pad to check, then when it looks good from all directions, mark each ‘ button’ clearly with pencil. To transfer the marks to the cushion, either make punched holes over the pencilled points and transfer the mark by pencil, or pin through the pencil points then transfer the marks with a second pin into the fabric beneath.

On the main fabric, mark each point securely with pencil, coloured tack or crossed pins. ( Pencil is Ok, as the mark will be completely covered by the button).

3. Mark the button positions on both the top and the bottom of the pad – it’s easy for the needle to go off course, so you’ll need the markers on both sides to keep the pattern good and reversible.

4. To make the buttoning pattern, work from the centre of the pad and always work from the same side.

5. Using a heavy duty or buttoning needle threaded with buttonhole or upholstery cord, push from the bottom through to the top marker. Leave plenty of cord free. Thread through the button or tuft and push the needle back through to within 3mm / 1/8 ” of the first hole. Thread the cord through another button, tie the ends together and pull tightly. Knot two or three times to secure.

Tip ! To button a thickly padded cushion, or to pull a stiff fabric in, wipe it with wax, then send the thread through the pad two to three times. Secure the thread ends with a spot of clear nail varnish.

Laundering

To clean buttoned pads:

a) snip the threads or cords holding the buttons in place, remove the cover and launder according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

b) stretch it back on whilst still slightly damp. Press and leave it on an airer to dry fully.

c) replace the buttons with new threads, stitching into the first stitch holes.

* If the holes have torn, look vulnerable or the fabric needs support, first add an interfacing to the back of the fabric cover; either pin in place to hold it there whilst you make the buttons or use fusible interfacing to bond to the fabric to secure a tear or worn edges.

Or replace the buttons with something of a larger diameter – perhaps wool tufts or circles.

Care and Maintenance

Careful and regular maintenance is the key to prolonging the life and maintaining the appearance of all furnishings.

External factors – your climate, water softness, linings, general use, all affect the level and quantity of care and maintenance needed, so there are few hard and fast rules. What we offer here are guidelines, encompassing experienced housekeeping knowledge, manufacturers advice and textile research results, which should be helpful.

Whether you do it yourself or not, a good and thorough clean, is therapeutic, and the traditional Spring clean routine is both sensible and very reassuring. The warmer, longer days as the seasons change enliven and energise us to put our house in good order for the summer, and for the long sociable evenings we hope to enjoy. Perhaps the higher sun spotlighting the neglected window cleaning, has something to do with it…

It’s good to know the house will be respectable for another year, even at the back of the cupboards and behind the pictures, and that all of the books have been taken out and freshened up.

To shake out the curtains and cushions, to beat the floor rugs and wash the loose covers, put away the winter bed covers, is all good. The air feels fresh, the house revived, spirits lifted. You feel ready for anything.

Textiles

A good spring breeze is the perfect remedy for textiles; furnishing fabrics in constant use take a battering from all manner of day to day soiling, which builds up over time. Airborne dust, smoke from fires or cigarettes will all blow out in a good cross draught. Washable covers and curtains dry quickly in a breeze and smell wonderful afterwards. Spring is a good time to wash out newsprint grime and marks from spillage and childrens sticky fingers.

Accidental spillage needs immediate attention. However, we need to remember that the damage is accidental and a big fuss can be embarrassing, so it’s useful to have some simple, immediate solutions to hand, even if only as a stop gap. A different matter If it’s children, or teenagers – they are probably somewhere they shouldn’t be, with coco cola, lollies or chocolate, in any case.

Traffic grime is particularly damaging and needs to be dealt with on a regular, and frequent basis. As you will quickly notice if you live in a city or close to a main road, window furnishings are deeply affected, but layers can also be deliberately employed to catch this dirt.

At the end of the day, you can’t go too far wrong if you treat your furnishings as you would treat a suit or ball gown – clean marks as soon as possible, and plan for regular cleaning and maintenance.

On a day to day level, air, and if not breeze then vacuuming, is the best preventative; it’s better not to allow grime to build up. Once dirt has penetrated the fibres it is much more difficult, if not impossible, to restore any textile to its former glory.

Our advice is: once a week, cover the end of the hand held brush attachment with a mob cap of muslin, which will protect even delicate fibres, and brush lightly over all furnishings. If this is done regularly it really doesn’t take long, as you are always only dealing with light dust. And cumulatively a lot less time than dealing with ingrained dirt.

Chairs and sofas

Cushion covers should be zipped and armcovers fitted with hooks and eyes, for ease of removal . The trick is to wash or dry clean just before it looks necessary, and long before grime becomes obvious. At that point it is ingrained, set and problematic.

Early on, every ‘spot’ shows, however there is a point at which, once the ageing process starts and fabrics begin to fade and take on a softness, a general change takes place, and mopping up the odd spot or area of wear, just shows that area up even more. Regular dry cleaning or washing are still the best solution.

The most common damage to the valances and skirts are a) shoe polish, which requires immediate cleaning with a specialist product and b) dogs, who choose to lie against the covers – frequent washing is the only solution to remove these natural oils.

Curtains

Light vacuum as for chairs – remember dust collects along the tops and spiders like the inside of the pleats at the back. Shake them well each time, and before you vacuum the floor.

Flies and spiders webs are always a nuisance and need to be discouraged before they leave black spots on everything – almost impossible to remove.

Our advice is to take advantage of any warm, breezy day. Open the windows and doors wide to create a through draught and give the curtains a good airing as they blow in the wind.

Spraying your favourite dilute linen water onto the linings keeps them smelling fresh.

Chemical cleaning, before the point when re-lining is necessary, does curtains no good, and is expensive. With a little day to day care, well made curtains will last, in situ, for decades.

All textiles are affected by humidity. The effects on fabric that spends it’s life between a warm room and the cold window can be considerable, as the main fabric, the interlining and the lining may well react to temperature change and absorb moisture in different degrees. The results show in the hems, and one of the good things about overlong curtains is the accommodation and disguise of all ‘dropping’ and temperature effect, particularly dramatic in ancient buildings, that can .

To minimise any ruckling in the seams It is very important to match the thread to the fabric – silk with silk, cotton with cotton, linen and a minimal, shallow, zig zag to relax the seams of wools, tweeds, and any open weave fabrics.

Re-Lining

If you have chosen your curtain fabric from your heart, depsite budget and invested in quality, you won’t want to replace it. Ever. We offer to re-line clients curtains every ten years or so. In fact, this month in our workrooms we have re-lined three pairs, all for different clients, all of which we made and have been hanging for around twenty five years. The cost of replacement has not been a factor; it is that the fabrics are still loved and are right for the place. Stripped and dry cleaned, with new interlining and lining they really do look as good as new.

Cities and roadside

We have noticed a very great difference between country and city curtains. The black grime from traffic gets right into the inner interlinings – even in rooms where the windows are rarely or never opened.

The very best protection we have found is from sheer under – curtains, as the fibres trap the dust and grime before it enters the room. It’s healthier for you too.

If you wash these sheers often – monthly in the city – you will be surprised at the colour of the water, and will see the difference it can make.

This is probably the only time I’ll recommend a synthetic material – but Jab international make a fine polyester which looks and feels good, it can be washed by machine and hung up damp, no creasing and no ironing!

Lampshades

Run the muslin covered brush over the surface on a weekly basis to prevent dust settling and discolouring.

Fly spots can be a nuisance and there is little that can be done about them other than regular cleaning or some sort of trimming disguise if they become a real problem but the shade still has a few years left in it. So, make a slip cover.

Fading

All fabrics do fade eventually, some colours are more prone to fading than others – pale tones especially blues and pinks always seem to go first. Especially on the floor, such as carpet directly in front of sun- filled windows

* It’s not just the curtains and window recesses which are affected by sunlight – papers and fabrics on walls adjacent or opposite are equally affected.

* Textiles dyed with vegetable dyes or home dyes are especially vulnerable and will fade long before those produced with vat dyestuffs. Vegetable dyed colours are softer and antique textiles especially need more consideration.

* Contemporary, commercially printed or dyed furnishings fabrics have all-round fastness, and good, inherent light resistance.

* Lining and interlining protects the main body of the curtain. Protecting the leading edges by drawing the curtains off the windows and away from light is rarely possible; sometimes closing them completely is the better answer.

* Lightweight sheers or Holland cloth roller blinds give proper protection and still allow you to control the extent and direction of day light.

* Shutters are another option. Slatted, colonial style shutters blinds are excellent if the room style allows; for a new build you might include pierced metal roll down blinds. If you don’t need the light especially, either solid wooden or pierced metal folding shutters work very well.

CLEANING

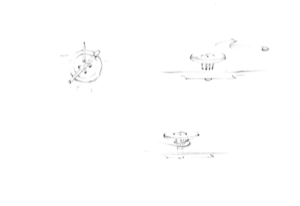

GUIDE TO CARE SYMBOLS

Washing

There are care symbols provided with every textile, and as these are the manufacturers directions, any other course of action becomes your responsibility.

However, It is my experience that many textiles marked for dry cleaning can be washed and we would always recommend washing all manageable items if at all possible. It’s less expensive, more immediate and often better for the fabric.

As always , the best way to know is to test. Take two 10 cm ( 4 ” ) squares, make one dirty, wash as hot as you need, and see what happens. Test for shrinkage, texture and cleanliness.

In our workrooms, it’s a matter of course, to test the fabric before cutting out. For anything fitted, like loose covers, we then either wash the whole lot, or make allowance to the cutting dimensions.

The problem with hand or machine washing is the retention of detergent, the presence of which causes fabrics to age and fade more readily. Very thorough rinsing is most important , as almost all washing powders and detergents contain some kind of bleaching or brightening agent, which can seriously affect the colours. Advice on specialist bought products needs to be current, fso or up to date advice contact the advisory service fro your fabric, listed at the end. wool, cotton , linen.

As a rile of thumb, any eco – friendly products or those suitable for baby clothes will be fine , as long as hey are strong enough to deal with the problem.

Mild liquid detergents such a stergene, woolite,

Some years ago we dropped a freshly made pot of coffee, including the grounds, onto a hand printed linen chair in the studio here. We whipped the loose cover off and machine washed it at 60o. Strong coffee is our fall back for ageing linen, so I was alsolutely prepared for disaster. Not a bit of it, no shrinkage and the cover even now looks as good as new. Co -incidentally a client took a cover in the same fabric to the dry cleaner and was very disappointed with the result.

Drying in natural air is best – outside on the line, or on a drying rack in the laundry / utility room

Fitted loose covers should be pressed and fitted whilst still slightly damp to get a good snug fit., and to stretch a fabric back into place which might have shrunk slightly.

Washing in snow really does work – the natural bleaching properties works wonders on whites. Lying whites on fresh snow is guaranteed to refresh them, as is laying whites on the newly dewed grass .

Sunlight is natures bleach – hanging whites out in the noonday sun is the age old way to keep linen fresh and sparkling white.

DRY CLEANING

All textiles come with cleaning direction – either as a separate label, or printed onto the selvedge. It its a separate label, paper or fabric sew or pin it out of sight at the back of the curtain

or underside of a chair cover.

Further advice can be obtained from:

The Association of British Launderers ,

The Dry Cleaning Information Bureau,

The Wool Secretariat

The Linen

WOOL

With proper care the natural qualities of wool can be maintained for many years.

Always press wool with a hot, dry iron over a damp fine cotton cloth, on the reverse. if you need to press the face, use the damp cloth, or another piece of the wool. Never press the face/ front without a cloth.

Making Up

If seams are pressed directly, the will mark the face, so always insert a strip of cotton or wool against the stitching line to press them onto( illustration p .. ) Some people recommend brown paper, but I find that’s bringing another material into the situation, which is less pliable and no more effective.

Wool cloth naturally ‘hangs out’ wrinkles and creases – especially useful where curtain tie backs are needed.

Wool can be steamed and pressed into shape – this property is particularly good for fitting upholstery and loose covers – careful attention and work can reduce the need for pleating and rucks can be steamed out.

A soft brush will remove and surface dirt without raising the pile. I find a damp sponge or cloth wiped over my flat weave wool stair carpets as effective, as quick and less damaging than the vacuum cleaner

If wool, covers or throws have become creased or ‘tired ‘, hang them on an airer with steam beneath or in the bathroom while you take a shower . A good tip for travelling overnight in the hotel bathroom with water left in the basin works wonders.

If wool has become wet, allow it to dry naturally, in situ if possible, with doors open and a through breeze to help.

STAIN REMOVAL

Wool is the easiest fibre to keep clean , which makes it an especially appropriate choice for flooring and upholstery.

Wool can absorb moisture up to 30% of its weight, which prevents the build up of static electricity, which in turn repels air born dirt and lint.

The natural oils provide it with the ability to repel water and stains, so most stains can be dealt with quite easily, by a spot clean on the surface, and there is a very useful short window of time in which to mop up spills before they soak in.

WASHING

Some wools are machine washable, most are hand washable, but the manufacturers instructions and a sample check are the only guarantees. Throws, cushions, bedcovers should be washed in lukewarm water with a specially formulated wool detergent , and plenty of rinses.

To dry, lay the wool onto a dry absorbent cloth, roll with the wool inside and twist gently to absorb as much water as you can.

Always dry wool flat, away from direct heat, in a ventilated space. Place the item onto a dry cloth over an airer, and carefully stretch back to shape if it shows any sign of shrinkage.

Press, and manipulate if you need to, whilst still slightly damp, over a dry cloth

IN STORAGE

The same chemistry that makes wool fibre resilient and durable, lets it breathe and shed wrinkles, also makes it attractive and susceptible to the moth.

The larvae feed on the keratin protein present only in animal fibres, where the cloth has been soiled with food stains and body oil.

Wool should always be brushed clean and properly cleaned before putting away, then packed in an airtight container. The colder the storage area the better, as long as it is also dry.

Herb sachets are essential – most of us have a few basic herb sin the garden that moths dislike- especially rosemary and lavender.

LOOSE COVERS

Loose covers can be tight fitted, loose fitted , or almost not fitted – whichever look you choose you will want your covers to look as good after cleaning as they were before. The shrinkage potential needs to be known.

As always, the best way to know is to test. Take two 10 cm ( 4″ ) squares, make one dirty, wash as hot as you need, and see what happens. Test for shrinkage, texture and cleanliness.

In our workrooms, it’s a matter of course, to test the fabric before cutting out. For anything fitted, like loose covers, we then either wash the whole lot, or make allowance to the cutting dimensions.

Washing the fabric once always shortens the time before it needs to be washed again, so that is a disadvantage.

Loose covers often last for several years before they need to be completely washed, but could be a a matter of months – a factor entirely dependent on the location and amount of use

Making up with the shrinkage allowance included will mean the covers being baggy and overlong until the first wash, so this approach is only really feasible if the covers are in a high use area and you anticipate early need – such as a playroom or kitchen / family room.

Armcovers

We make full sized arm covers; these fit right to the back of the arms to the side / back seam, tucking under the back cushions or into the arm – back junction. The inside arm extends as far as possible, tucking in to the seat / arm junction. The outside arm finishes either along the top of the valance or to the floor, as appropriate.

Discrete hooks and eyes fix the covers in place. Most armcovers aren’t washed that frequently, so we usually slip stitch the cover to the back seam , which really does render them nearly invisible.

For hard wear sofas a square that is large enough to tuck in over the seat cushions is a good plan, and sometimes one for the back as well. Or separate back covers. These can be easily taken off for washing, back on in the same day.

“SCOTCHGUARD’

There are now very good waterproof sprays which can be applied to fabrics in situ or during the manufacturing process, which are invisible and hardly alter the feel or appearance . We are used to using these on shoes and handbags, on suede coats and leather bags; to have the same for high wear areas in the home is clearly advantageous.

FABRICS

Before you even pick up the scissors, check that the fabric is – the colour and pattern that you order, the pattern repeat is close to that ordered, that it feels right and that the finish is as you expected. Roll it off and check for flaws and that the total length is as ordered.

Usually you’ll have been given a few centimetres more.

There might be hanging tags clipped into the selvedge These indicate the presence of flaws. Check that this flaw is acceptable, and that the extra fabric which you will have been sent as is adequate for your needs and you can get your cut lengths out intact. Once you’ve cut into it, you won’t be able to return it.

Always order all the fabric you need at any time; as with knitting wool, if you run out, it is almost impossible to secure the exact match again.

If it is critical that the colour you order must be the same as the sample you hold, always ask for your piece to be reserved whilst you check that a ‘ stock’ cutting from the same roll will fit your purpose,

As a matter of policy, we always confirm a stock cutting before finalising the order. At the same time we take the chance to request the lightest, or darkest of the current stock, if that is, for our use, preferable.

Pattern

Pattern repeats are rarely exactly the same throughout and good size of roll, so you may find that the lengths do not easily join , or that if they do, the hemline ‘runs out’ across several pairs of curtains.

You’ll need to go with the pattern even if this goes against the grain of the fabric. If the pattern is very far out, firstly, try to return it to the supplier.

If you need to work with it, then extra weight in the corners should pull the leading edges and the returns into line within a few weeks.

Chintz

This finish , which gives a light glaze, sheen, over the fabric surface is usually susceptible to

water damage, in which case it should only be pressed from the back, or on the front with a dry iron over a dry cloth. To remove any creases the iron will have to be very hot, so use quickly. very stubborn creases might need a little steam – test a piece first, and if the glaze does not disappear, use the least damp cloth you can beneath a hot iron. if you try to use the spray from the iron, you could well find that the glaze just disappears in spots where the water hits, which is both unattractive and irrepairable.

It can happen that a fabric has been ‘over chintzed ‘. It will crack at every crease which is hopeless as , however careful you are , in a domestic situation, you can’t avoid some light creasing as you move the fabric around. Cracked chintz doesn’t look as beautifully aged as a light chintz might, it just looks a mess.

We often stretch the cuts to bring them back into square, but that isn’t usually possible in a domestic situation.

Cutting out

It’s always exciting to start a new project – and the process of cutting out is a sort of ritual – it’s the first step – an ordered, collected process, with everything in it’s place. You need the space, tools, a clear head and time enough to concentrate.

Furnishings generally don’t require paper patterns, although for chair seats and windows seats, pelmets and lampshades, there will be templates or toiles to follow. Most are made of rectangular pieces of fabric cut to the dimensions suited to your bed, window etc. Whilst no project is ever the same the techniques generally involve straight lines, so in general our projects tend not to have patterns or cutting layouts to follow; however, our basic technique sheets supply clear planning procedures and occasional guidelines.

With a patterned fabric, pieces are very often dovetailed – cut between each other, to minimise potential wastage within the pattern repeat, e.g: pieces for loose cover skirts, pelmets or cushion gussets can be cut between each other or between curtain lengths. How this works out will inevitably be different for every project. When a cutting layout is supplied it is either to be followed rigidly, or used as guidance for fabric economy – the project notes will clarify which is which.

More than anything, great furnishings depend on precise cutting, and this is best achieved by measuring and working from the outer edges.

* Firstly, always check that the length on the roll is as the length on the delivery note , and the length you ordered.

* Check the pattern repeat is as you expected – they vary – and any variation can affect the amount of cuts and how you planned to cut the length – you might just need to adjust your hem or heading allowances, or revise the whole cutting plan.

* Plan the starting point – where the hemline will be to best suit the pattern

* Look to understand your pattern – how it repeats, matches, drops and runs – see pattern matching

* Check for nap – even if it looks non- existent, it could just be very subtle – any surface variation shows more made up than when flat

* Look to see whether it can be railroaded if you decide it might be a better to cut any projects of parts.

* Measure out each length – each cut as per your cutting plan – and mark the selvedge with pins to make sure that you have the correct amount of fabric for the project. If you – or the supplier – has made an estimating error you can often correct it at this stage.

* If flaws are tagged, watch out for these and avoid them. Check the supplier has sent enough extra allowance.

* Try to plan the cuts around simple line flaws or to incorporate them into headings and hems.

* Mark the whole roll and denote each cut with pins and then snips before you cut out

* Measure twice – or many times – cut once.

* Always use very sharp scissors

* Only cut with the fabric completely flat . The fabric must be cut on the table, smoothed out and pinned to the worktable with one selvedge along one long side of the table. The easiest way is to now sweep the ruler over the cloth to remove minor creasing and folds, press to remove any firmer creases.

* Trim the short end of the fabric straight, and at right angles to the side; follow the bottom edge of the table.

* To make sure each cutting line is straight, measure up from the bottom of the table approximately four times across the width and join the pinned markers with a pencilled line , or score across it with the point of the scissors.

* Always cut with fabric flat on the table, don’t lift it off or try to cut it without flattening it.

* Always cut with one hand resting on the fabric and positioned just in front of the scissors.

* Always mark the top and the right side, of each piece as you cut it – we use crossed pins, but a tailors tack or angled double snip – anything which is easy for you to get into the habit of doing – this practice should become automatic.

* Keep the cut lengths as flat as possible – lie them on another table, or over a bannister rail, or the curtain pole until you need them. Try not to fold your lengths at all but if you do need to fold, then always lengthwise.

* Once the seams are joined, hang the curtain or keep it flat again.

The Grain

Fabric should ideally be cut along the grain and to pattern, but sometimes the printing method – and industry tolerance – allows the pattern to move off grain. In which case, make sure that the leading edges of all pairs of curtains are exactly the same – that they match at the centres. If necessary allow the pattern to run out slightly to either side but a 2 cm run – off is the most you should tolerate.

Do not be tempted to follow the pattern and cut off the grain as the curtains will not hang straight. As you cut each piece, mark the right sides and the direction of a plain fabric just in case there is a weave variation which is not noticeable until the curtains have been made up and hung.

Flaws

Before you start cutting check through for flaws. All fabric suppliers will have tagged the selvedge to highlight any flaws, and sent some extra length, however we do often find other things we don’t like- small holes, or a slub in the weave which have either passed their test , or unnoticed. We never cut out unless we’ve first checked the whole length – and not a mistake you’ll make twice.

In a large metre-age of fabric there will certainly be flaws, however if you are prepared – knowing your cuts and what you can work around, and to spend a little bit of time – you can almost always find a way to cut around them – or at least minimise the placement.

Of course you can always return the fabric for exchange , but that can be very inconvenient, both physically and emotionally – usually if you’re at cutting out stage you really want to get going. And who is to say the next piece will be any better.

What is for sure is this – the better quality the fabric you invest in – the more you pay – the less chance of a flaw, the more chance the cloth will be on grain and beautifully printed or woven. Over the last thirty years, every single trainee, once they are allowed to work with the serious fabrics , has commented on the difference. The sound of the cloth, the sound of the scissors on the cloth, the feel of it, the way it cuts , and the general manageability. You need the best wool flannel for a Saville Row suit – you can’t make it out of a dust sheet. For curtains, you can use either – as long as you keep the possibilities and the results clearly in perspective.

USING THE PATTERNS

* Lay out all pattern pieces before you start cutting

* Pin patterns to the cloth every 7- 10 cms , all around the edges and often enough to keep them flat onto the fabric ; pin at right angles to the pattern piece and approx. 1 cm within the edges and again further back and parallel to the edges for larger pieces. Pin more often towards tricky points and diagonally at corners.

*For soft and slippery fabrics, many more pins may be needed.

* Also always cut only one layer at a time, don’t be tempted to fold fabric to cut pairs as the layers just slip against each other.

* If you’ve made a mistake and end up with a very wobbly edge and no fabric spare, pin the pattern on again – this time properly – and re-cut it within the seam allowance. Just make a note to make this piece up with smaller seam allowances.

* Make sure any grain lines are exactly on grain

* Cut single or grouped notches or snips into the seam allowance to denote important points and for later matching up. When you have two similar shapes to match – for example the backs and fronts of cushions, make random groups of notches so that each of the sides is unique.

* Treat all cut pieces with care. Only fold if necessary and then only lengthwise. Drape curtain lengths in waiting over a bannister, a bed , dining table or along the side of the worktable, fold in half and then in half again. Never fold curtaining widthwise.

* Keep all scraps – look at ‘From the Cutting Room Floor’ to see how much fun you can have with cast offs, even with frayed threads.

Dressing curtains

A client once suggested that dressing curtains- and fitting loose covers- were like fitting a ball gown or a couture frock – a really essential part of the process that can make or break the hard work thus far.

Hand headed curtains need to be dressed as soon as they are hung so that the pleats are trained to fall evenly. A little patience at this stage – you will need to be able to leave the curtains tied back for at least 48 hours and possibly up to 96 hours for a determined fabric – will ensure well behaved curtains that will always hang well, with pleats thatl fall into place each time the curtains are pulled.

Gathered curtains need some help too, especially to encourage the headings to fold back neatly between the hooks, but as they should be less formal looking we tend to pleat them up as below but to let them go after a couple of hours.

To make curtain look settled, and even less formal, we open and close them many times ( a couple of hundered ) so that the fabrics are a bit softened and slightly relaxed. Steaming them lightly beforehand also works.

1. You need to be standing as close to eye level as you can get for each process. With the curtains in the stack-back position make sure that the heading is in order, pleats forwards and the gaps folded evenly between each pleat. If the curtain hangs under a track or pole, the gaps will fold behind, if in front the gaps will be folded to the front. Some headings e.g. goblet pleats will only look their best if the gaps are folded behind.

2. Take each pleat and smooth it down through the curtain as far as you can reach to form each pleat into a fold.

3. Now standing either on the floor or lower down the step ladder, start at the leading edge and follow these pleats through to waist height. From the leading edge fold each pleat back onto the last to form even pleats. Once they look neat and well formed, tie a tape or strip of fabric loosely around the curtain to hold the pleats in place.

4. Kneeling on the floor, follow the folds through into the hem. Finger press the hem firmly.

Heavily interlined curtains need to have this fold formed very firmly, or the hem will ruckle between each fold. If the curtains are overlong, keep the pleats together and bend the curtain to one side for now. Tie another tape or strip of fabric around the curtain hems to hold the pleats in place, loosely enough not to mark the fabric, but tight enough that they do not slip down.

5. Check that the pleats are comfortable. If one or two seem twisted, adjust them. Springy fabrics may need to be re-adjusted several times, but will become easier each time, as the pleats are trained.

6. Tie another tape or strip of fabric loosely around the curtain, just below the headings, to hold them in place.

The best material tie to train the curtains is a flat tape – we’ve found that slicing up the polythene tube that we use to transport them in is our perfect solution. The cost is negligible and already factored in, with the advantage that being clear they ties themselves don’t detract from the new, beautiful, curtains. Strips of fabric or woven heading tape are the other options. Clients are usually pretty good at leaving them in, however much they want to enjoy them – and they soon learn how to put them back again if they do use them; after some hours the fabrics have ‘learnt,’ quite a lot, so it’s not that hard to do.

Hem finishes

The quality of the hem tells it’s own story. And that’s as true whether referring to the hem of a skirt, jacket, curtain or lampshade. Hem lengths ( in curtains as in skirts ) might go in and out of fashion, but creating a good, well constructed hem is all about about technique, and precision. One of my bete noires is a poorly conceived hem. From a design or a making perspective, and how it looks when lights shines through. Any bulkiness or unevenness, or mis-matching or dark colour behind always look really bad under the light- to such an extent that it can completely spoil the rest of the hard work.

So, all raw edges must be well cut and trimmed, and always be tucked right into the folds as it’s from here that any unevenness will be revealed. Take special care with blinds, short curtains and pelmets that actually hang in or just in front of the window, directly in front of broad daylight.

Where it’s appropriate, a simple applied or hand worked finish can change a plain hem, and therefore the whole project, beyond measure, elevating it to a level of importance and meaningfulness that only design input, hand work and consideration can really do. A simple linen sheer, for example, is just that – until the edges are finished with carefully spaced French knots, or several rows of hand stitching or other embroidered stitching – all white on white, subtle, but the whole thing has changed.

Standard hem

Firstly hems need to have enough weight in them to make a difference – small hems will roll; unless they will be completely hidden and the bulk is too much, all hems for sheers and unlined curtains should be double folded. So a 3 cm ( 1 1/4″ ) hem needs to have an allowance of 6 cms ( 2 1/2″ ) -i.e. to create two folds of 3 cms ( 1 /14″ ). It’s generally better to show the stitching- whether executed by machine or hand than to slip stitch, which isn’t really secure enough for furnishings over a long length.

Each project has it’s own hem explanation, especially when it varies from normal, and most are OK left with the stitching line alone showing, but sometimes a bit more detail can help and broadly these are a few basic finishing options.

Double stitched

Either stitch the hemline with a double needle or follow the first line with another one, using the machine foot as the guide.

Hand Stitched

Hand stitch the two outer edges or the whole width of the hem – with shorter or longer stitches in a single, double, triple or more rows and in matching, complementary or contrasting threads.

With tape or ribbon.

Almost any ribbon in any width can be used as long as the weights of fabric and ribbon are compatible. If the fabric is reversible, you could set the ribbon up from the hem. If not, make the bottom edge of the ribbon the hemline.

1. Press the hem allowance (usually 1.5 cms) to the front. Place the ribbon over so that it fully covers the raw edge and lies parallel to, or along, the folded edge. Pin along the centre and then across the ribbon- these pins will remain in place during the stitching.

Join the ribbon ends by folding under one end to overlap the other – handstitch the gap closed with tiny stitches if there is any gapping.

2. Top stitch or hand sew over the ribbon as close to each edge as possible. Remove the pins and press.

Shell Hemming

Shell hemming is a neat and quick finish. It’s all done by hand without pressing and can easily be done without measuring and pinning. Roll a double hem to just 0.5 – 0.7 cm ( 1/4 – 5/8″ ) and pin (rather than pressing). With matching thread, make a double stitch at right angles to the hem, finishing just on the folded edge. Slide the needle along the fold for 1.5 – 2 cm ( 5/8 – 3/4″ ) and make a small stitch on the inside to secure. Make the ‘shell’ shape by taking the thread around the hem, then pushing the needle straight through from front to back. Pull tight. Repeat and then slide the needle along the fold for 1.5 – 2 cm ( 5/8 – 3/4″ ) to the next stitch.

Embroidered hem

Many simple embroidery stitches can be used for a decorative finish to a folded hem. The basic stitches such as blanket stitch, chain stitch or a coloured thread running through a machine stitched line are all easy to do, effective finishes that don’t demand too much time.

How it works

Taking an idea and making it reality, making it happen, takes commitment.

Each project comes with the necessary information to create the photographed item, and with some suggestions of how it mitt be use or made otherwise. However, to avoid constant repetition and to keep the instructions clear, we have set out the techniques in full detail in our Basic Techniques Library. These cover everything you need to know – to do with the workroom and setting up your own space, choosing and selecting materials and the detail of procedure: why it matters, what to be rigidly particular about and what can be left to an in situ decision.

The Design and Make series presents the principles and methods of tradition, artisanship and craftsmanship with new ideas and purpose. The core principles that have been tried and tested over the past thirty years in our soft furnishings workroom and taught in our courses and workshops are always the ground, the basis for all projects and suggestions. Couture, pattern cutting, dressmaking, tailoring and upholstery skills and techniques are all referenced and well represented.

All craftsmanship relies on a set of learned methods, and there is no substitute for experience and practise. In following these age-old techniques we have learnt, honed and built skills that allow us to create and adapt with ease and confidence, to make successful projects with enthusiasm and enjoyment.

These guidelines are there for you to follow step by step if you’re a beginner, or to refer to if you’re just a bit rusty.

Design and Make Projects

All of our projects have been taken directly or indirectly from furnishings that we have made for clients.

Design

A few notes on the design shown and suggestion for the materials you can choose or use:

Materials

The materials and sizes used include, as appropriate:

- Cutting plan

- Chart for alternative sizes

- Pattern sheet than can be enlarged or adapted

- Cutting and materials list

Prepare

- Work neatly from one end of the table to the other, always fold materials that are not being worked on.

- Have all the pins, rulers, threads and needles, etc. close by and in one tray.

- Start with all of the cutting out, seaming and pressing – everything that requires a clear, flat table surface.

- Make up and prepare all of the small items and trimmings – everything that you’d like to have finished and ready to hand when you need it.

- Make all eyelets, buttonholes and embroidery details in one sitting to keep the stitching consistent – even a day between can visibly affect the end result.

- Keep the iron by your side and press at every stage. Press over the stitching line and press seams from the right side to embed the stitches.

Making up

- Work methodically and neatly. Enjoy the rhythm and order of the process and the therapy of hand stitching.

- The order of work has been carefully put together – follow the instructions and you won’t fail.

- Try to make the time to finish each stage in one session; if this is not possible, leave the work in place on a large table / somewhere you can easily come back to.

- Plan your schedule to accomplish as much as you can each time; the longer you work, the faster you’ll get and it will feel concise rather than endless.

- Make an effort with the finishing details – neatening and trimming seams and corners – this might not seem that important, but it makes a huge difference to the end result, professional finish and compliments you’ll receive.

Hanging and Fitting

Refer to the Guides and Techniques Library for fitting and hanging, dressing curtains.

- Well-made furnishings can be let down by poorly considered fitting and careless hanging, whilst paying attention to such details makes fabrics look their very best and raises less well made furnishings up a level.

How to make perfect furnishings.

Our project collection contains really good ideas for furnishings that are quick and easy, which take little work and can be made without a sewing machine. These are not by any means second rate, they’re for all of us who are short of time–after all elaborate or complicated furnishings are not necessary in every space. Some of my favourite rooms are the simplest, and require few sewing techniques.

However, if you want to make things and have little experience with textiles, it’s not a bad idea to embark on a short course in any of the skills mentioned below, in order to gain the experience and knowledge that will add more strings to your bow. Whatever your previous skills, choose something that is within your capacity, yet with some aspect that which will stretch you a bit further.

My list of guidelines for making perfect furnishings is:

* Make up the most simple and least expensive fabric well and it’ll look a million dollars. Make up a great fabric carelessly and it’ll look like a dish rag.

* Never compromise on the quality of the fabric or any of the supporting materials.

* If you have little or no budget: buy good quality ends of rolls, remnants, off-cuts and old pattern books to make patchwork. Use blankets and sheeting, towels and even dust sheets for curtains and covers. Re-use torn sheets for cushions and pillows and adapt old curtains with imagination and edgings. Find denim, ticking, calico and gingham, all of which cost a few pounds a metre and dig out your odd balls of wool–or buy them for next to nothing and knit something.

* A little of a quality piece, whether new or an antique, goes a long way: buy one great piece and use sheeting or something simple for the rest .

* Make sure the design of a lampshade, chair cover or curtain compliments the surrounding space.

* A fabulous pictorial design should be seen, when the fabric will be gathering, as it will loose its glory and effect: instead use it flat and sparingly.

* Fabrics for a purpose, that enhance; make sure that they drape, or fold, or pleat or gather as they ought.

* All materials used together are fully compatible.

* Always make a test piece so that you know your materials i.e. how they reacts to steam, damp, washing.

* For anything new or unproven always make a toile – a fabric pattern, from muslin or calico to determine and confirm the exact shaping, size, and making method.

* Pay proper care to the fittings–for 99% of projects keep them as simple as possible, you’ll know when you need to push the boat out!

* Use the right size and type of needle and thread, and change the needle frequently.

* Use sharp scissors.

* Press at every stage and keep the iron always at your elbow.

* Measure everything– and keep measuring.

* Headings and any detailed finishes must be in proper proportion to the given space and to the other objects in the room.

* Every detail should be conceived with due care and consideration to the fabric and to its environment.

* All lines should be even and equal, especially those of bindings and borders.

* All edges should lie smoothly, shouldn’t ruckle, or drop at any point in time.

* With the right under-linings, interlinings, stitching and the right pressing techniques, hems and edge works should be invisible.

* Techniques such as pleating, making tucks and buttonholes must be made with precision, or not at all……

* All decorative finishes including embroidery, and beading, should be done with a confident, free mind; within a framework but with artistry and emotion.

Again!

If you want to make something well and to make it special, you need to be prepared to spend some time on both the design and the execution, to learn some new skills and to persevere with the difficult bits. Practice does make perfect: good materials and tools and a dedicated space also helps.

Dressmaking and tailoring skills undoubtedly provide invaluable help with areas of basic knowledge and an ability to handle layers of material–with knowing how it should feel. However rudimentary, a knowledge of pattern cutting, adapting, draping and design are also helpful.

Furnishings require the same skills, but they are often used in a different way and over longer lengths. As furnishings can be heavy, hems and seam allowances are made and finished differently; finishes such as piping, which are rarely used in dressmaking are one of the staple techniques of furnishings, as are binding, pleating and gathering: ties, buttons, buttonholes and eyelets are used in favour of zippers. Tailoring techniques are particularly helpful in fitting fabric to a form or substructure.

When I transitioned from couture to the straighter lines of soft furnishings I had a good working knowledge of the above skills, so was able to produce perfectly ‘good enough’ work. What made all the difference was my experience working in the West Country–farming territory– where things were originally bought and made to last. It was in the taking down, replacing, repairing and undoing of furnishings that had been made by the top London houses many years before, and which were literally shredding to pieces, that we really learnt how ‘to do it’. We stretched our horizons and learnt by trial and error–we’ve made all the mistakes and tested many ideas and methods to achieve our current highest calibre work.

Upholstery skills can help to a certain extent, however upholstery fabrics are treated and worked in such a different way, being pulled and stretched into place, that it can sometimes be a hindrance. With loose furnishings there is no hiding place; every nip and tuck, dart and pleat has to be worked into a flat piece of cloth: puckering can’t be stretched out or corners pleated and fixed to another surface.

Have Fun !

Heather

Interlinings

CHOOSING INTERLININGS

Interlinings are in effect under-linings as they are made up with the main fabric as one when the work is small enough, or attached after seaming when the area is large, such as with full-length curtains. The primary purpose of interlining is to add enough body to make the top fabric lovely and thick, padded and luxurious; the weight of the interlining defines the look and affects the drape. In addition, thick curtains block light and draughts, and work well on uneven stone and wood floors. They enclose and envelop.

Most furnishing interlinings are woven from either cotton or synthetic fibres (sarille) and are available white or unbleached, in light, medium and heavy weights. Sarille of any weight holds well to most top fabric and takes about half the time to make up than its cotton counterpart: all in all, working with sarille is a less bulky and easier to manage process. Cotton interlinings are heavier and a bit more onerous to work with, but give a more convincing and traditional finish.

Other interlinings, such as polyester wadding, very fine foam or wool felt can be used for curtaining and pelmets, but are mostly used for flatter works such as quilting, to support appliqué and make padded upholstery.

* All interlinings can be used as quilting mediums; although perhaps too heavy for bedcovers, they are good for quilted upholstery sections and flat panelled bed valances.

* The fine lightweight cotton interlining called domette just adds depth and a lovely roundness to lightweight top fabrics; use for heavily gathered and draped furnishings, pelmets, swags and tails and bed valances to add body, and as a quilting medium.

* Domette interlined curtains remain light enough that they can still be swagged up and draped, which is especially good for Italian stringing and tie backs.

* The heavier cotton interlinings are called bump and work with even the heaviest of textiles to make really weighty curtains.

* Heavily interlined curtains look good sitting well onto the floor, and in doing so cover up a multitude of floor and draughty window problems.

* Consider how you plan to launder or clean the furnishings, as the three layers of top fabric, interlining and lining all need to react the same when laundered.

* Interlining for short curtains should be of the finer and lighter weights so that the hems don’t become too bulky and still sit well without the floor to help.

* Interlining Roman blinds makes them into more solid looking, padded draught-proofers.

* Interlining wrapped over foam, rubberised hair or traditional horsehair upholstery add a layer of softness without looking over-padded. Use for window seats, settle cushions, headboards, squab cushions, upholstered stools, screens, chair seats and backs.

* White interlining is the best for all light ground and white fabrics, otherwise and for most uses unbleached interlining is fine.

PREPARING INTERLININGS

Using curtain makers interlinings, but in fact anything thick can be used – from old blankets, old wool curtains to oven glove lining, to duvets.

Cutting Out

** Interlining should be cut out following the grain – if at all possible. Failing that, lie it on the table with the top on one short side and one selvedge against the long edge, smooth it out , and cut the hem along or parallel to the other sort edge.

** Always snip the seam allowance at an angle every 5-6 cm ( 2 – 2 1/2″ ) along each edge, with cuts of just about 1.2 cms ( 1/2′ ) – you can feel the slightly tight selvedge beneath the fluffy finish. This will stop the edges pulling as they undoubtedly will as the main body drops s a little under its own weight, and as it acclimatizes.

Joining

Any machined interlining joins need to be stitched with a half – one zig zag stitch. Interlining, and all the fabrics involved will drop or adjust themselves, and this little lea-way in the stitch allows the seams to move just enough that you won’t see the layers pulling against each other in a couple of years.

Railroading

Interlining seams are best avoided if at all possible, for all small items, and so for bedvalances, short-enough curtains and blinds, pelmets, bolster covers and quilting projects we cut down the length. This tends to be not only the easiest, but often the most economical, and always so in terms of your time.

Curtains

Heavy interlinings, medium interlinings and ‘bump’ for curtains should be hand joined in the making. It takes no longer, can be easier to manage, and is far more accurate – it’s no fun trying to machine stitch big heavy interlinings – it’s hot and bulky, and the seam allowance will almost undoubtedly slip.

It is very important that all interlining seams match the curtain seams, so the widths might need to be adjusted, which again is easier to assess accurately, on the table, as you are making.

Synthetic interlinings, conversely, are generally easier to manage and may be joined before use – either with well pressed or with overlapping seams.

Walling

For walling,the seam do need to be pre-joined, in sections by wall. In which case we use flat seams with a 4 cms ( 1 1/2″ ) allowance which reduces the likelihood of the interlining causing a ridge in the walling. Either machine stitch either side of this overlap with a loose stitch or zig- zag, or handsew – press, then herringbone or long stitch either side of the seam. the overlap.

Or for the very best job, the seam can be overlapped as with curtains and stitched in situ with long stitch- secure the top and bottom with temporary tacks, sew the seams, then fully upholster. With walling, the top to bottom needs to be taut, but the side to side doesn’t have to be under so much tension.

Pelmets and Bed valances

We do occasionally machine stitch either domette or sarille for short lengths – always with an overlapping seam, zig zag stitch and snips as mentioned above. This would always be for a specific purpose or in extremis – usually we railroad, or we would hand stitch .

Bed covers

Always hand seam, use sarille or domette and overlap the selvedges.

Stitching in